Analyzing Judicial Selection In Texas

The following is excerpted from the TLR Foundation’s recent paper on judicial selection, entitled Evaluating Judicial Selection In Texas: A Comparative Study of State Judicial Selection Methods. The full paper is available at www.tlrfoundation.com.

A young Abraham Lincoln, commenting on the recent passing of the last surviving Founding Father, James Madison, urged his audience to “let reverence for the laws… become the political reason of the Nation.” He observed that all should agree that to violate the law “is to trample on the blood of his father,” and that only “reverence for the constitution and laws” will preserve our political institutions and “retain the attachment of the people.”

Lincoln knew that the law is the bedrock of a free society. Our judges are the guardians of the rule of law. If they do not apply the law in a competent, efficient, and impartial manner, trust in the rule of law will erode and society will fray. Therefore, our system for selecting and retaining judges should be based on merit and should encourage stability, experience, and professionalism in our judiciary.

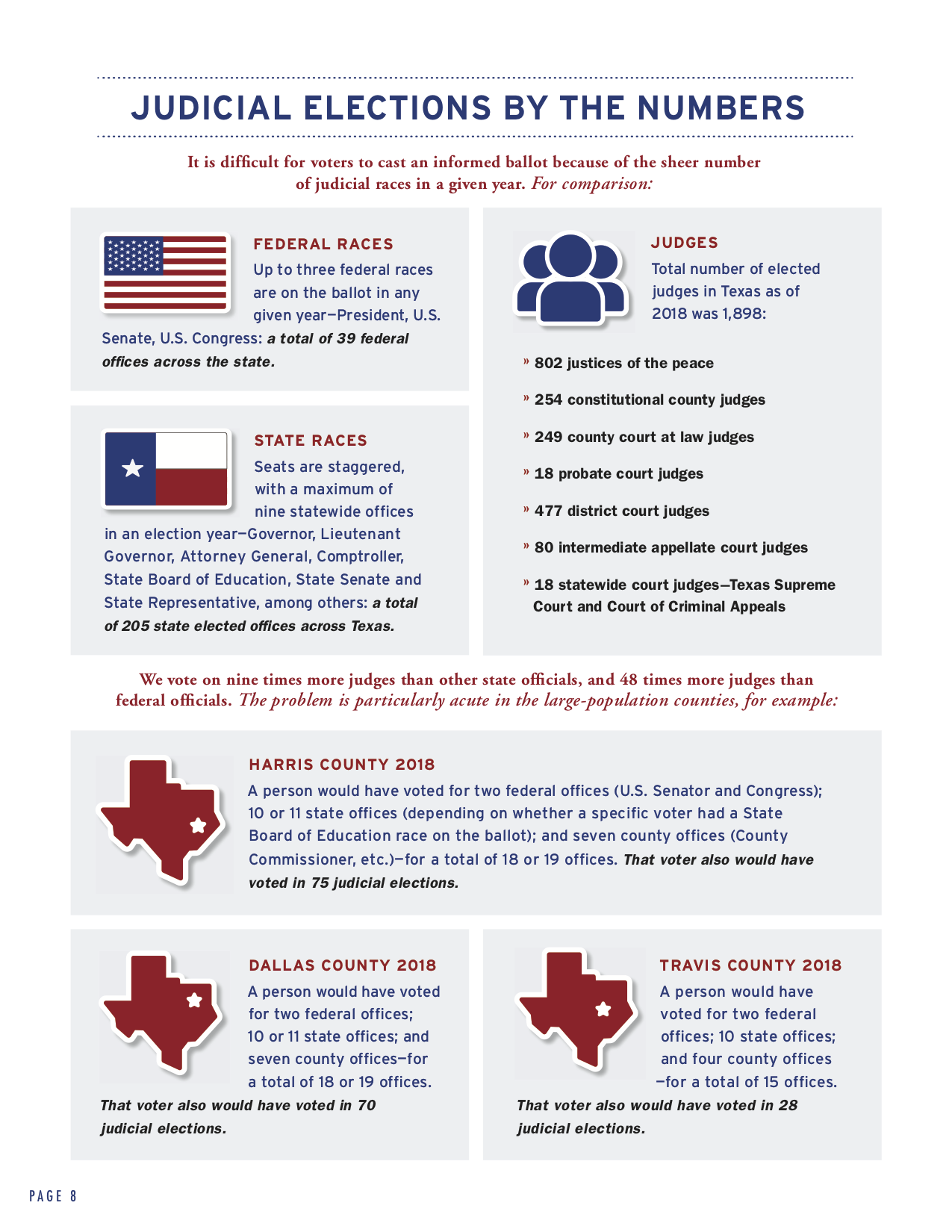

Our current system of partisan election of judges does not place merit at the forefront of the selection process. How can it? Unquestionably, most voters—even the most diligent and informed ones—do not know the qualifications (or lack thereof ) of all the judicial candidates listed on our ballots. This is especially true in our metropolitan counties, where the ballots list dozens of judicial positions. And even in our rural counties, voters are asked to make choices about candidates for our two statewide appellate courts and our fourteen intermediate appellate courts with little or no knowledge of the candidates for those offices.

The clearest manifestation of the ill consequences of the partisan election of judges is periodic partisan sweeps, in which non-judicial top-of-the-ballot dynamics cause all judicial positions to be determined on a purely partisan basis, without regard to the qualifications of the candidates. A presidential race, U.S. Senate race, or gubernatorial race may be the main determinant of judicial races lower on the ballot. These sweeps impact both political parties equally, depending on the election year. For example, in the 2010 election, only Republican judicial candidates won in many Texas counties. In 2018, the opposite occurred and only Democratic judicial candidates won in many counties. These sweeps are devastating to the stability and efficacy of our judicial system when good and experienced judges are swept out of office for no meritorious reason. Nathan Hecht, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Texas, described this vividly in his State of the Judiciary Address to the 86th Legislature:

No method of judicial selection is perfect… Still, partisan election is among the very worst methods of judicial selection. Voters understandably want accountability, and they should have it, but knowing almost nothing about judicial candidates, they end up throwing out very good judges who happen to be on the wrong side of races higher on the ballot.

Partisan sweeps—they have gone both ways over the years, and whichever way they went, I protested—partisan sweeps are demoralizing to judges, disruptive to the legal system, and degrading to the administration of justice. Even worse, when partisan politics is the driving force, and the political climate is as harsh as ours has become, judicial elections make judges more political, and judicial independence is the casualty. Make no mistake: a judicial selection system that continues to sow the political wind will reap the whirlwind.

And there is this: judges in Texas are forced to be politicians in seeking election to what decidedly should not be political offices. They are not representatives of the people in the same way as are elected officials of the executive and legislative branches. A state legislator is to represent the interests and views of her constituents, consistent with her own conscience. A judge is to apply the law objectively, reasonably, and fairly—therefore, impartiality, personal integrity, and knowledge of and experience in the law should be the deciding factors in whether a person becomes and remains a judge. A judicial selection system should make qualifications, rather than personal political views or partisan affiliation, the paramount factor in choosing and retaining judges.

Over the past twenty-five years, Texas has led the way in restoring fairness to our civil justice system. We now have the opportunity to lead the way in establishing a stable, consistent, fair, highly-qualified, and professional judiciary, keeping it accountable to the people, while also increasing integrity by removing it from the shifting winds of popular sentiment, electoral politics, and the need to raise campaign funds, all with the knowledge that the truest constituency of a judge is the law itself.

Partisan Elections Gone Wrong: Case Studies

The Great Partisan Sweeps

Urban areas in Texas have experienced alternating party sweeps in which judicial candidates from one party were uniformly elected to office based on party affiliation, and later defeated for the same reason. The popularity of the candidates at the top of the ballot often becomes the deciding factor in judicial elections. The pendulum has swung back and forth over the decades.

When Democrat Lloyd Bentsen ran for reelection to the U.S. Senate in 1982, Democratic judges fared well. When Republican Ronald Reagan ran for reelection as president in 1984, Republican judicial candidates were more frequently elected. In 1994, Republicans in Harris County won 41 of 42 contested county-wide judicial races. In 2010, Republicans in Harris County won all 65 contested county-wide judicial races. In 2018, Democrats won 31 of 32 contested courts of appeals races in a partisan sweep that was impacted by the U.S. Senate race between Republican Senator Ted Cruz and Democrat challenger Beto O’Rourke.

In the 2018 election, five statewide judicial races featured both Republican and Democratic candidates. If voters were basing their decision on judicial competence and not party label, one might expect the margins of victory to vary from race to race. However, in these statewide races—three for the Texas Supreme Court and two for the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals—the prevailing candidates were all Republicans and all had nearly identical margins of victory.

Criminals on the Court

In July 2019, a federal jury convicted Rudy Delgado, a suspended justice on the Texas 13th Court of Appeals (Corpus Christi), of eight criminal charges stemming from his acceptance of bribes and obstruction of justice when he was a state district judge.

Before being indicted in February 2018, Delgado had decided he wanted to move up from the trial court to the court of appeals. After being indicted, he was suspended from his seat on the 93rd District Court by the State Commission on Judicial Conduct, but his name was not removed from the November 2018 ballot due to a technicality in Texas election laws. Despite being under indictment and suspended from his judicial seat, and despite essentially abandoning his campaign, Delgado defeated a well-qualified Republican and won election to a seat on the court of appeals. He was promptly suspended, again, by the Judicial Conduct Commission and ultimately removed from office after his conviction.

Delgado’s indictment was not a secret—it had been widely reported for months in the local news leading up to the 2018 elections—but it did not seem to matter. He was elected to the court of appeals in 2018 because he was a member of a particular political party, and for no other reason.

Another famous example is the case of Don Yarbrough. Yarbrough ran for the Texas Supreme Court in the 1976 Democratic primary against a highly respected incumbent. His name was easily confused with those of the well-known gubernatorial candidate Don Yarborough and the long-serving U.S. Senator from Texas, Ralph Yarborough.

At the time of election, Don Yarbrough had been sued at least 15 times and was the subject of a disbarment action alleging various legal violations and professional misconduct. Despite a great deal of media attention, a survey revealed that 75 percent of voters were unaware of Yarbrough’s controversies.

After he was elected to the Texas Supreme Court, he was indicted and convicted of lying to a grand jury and fled the country. He was eventually captured and returned to the U.S., where he spent six years in prison for bribery.

What’s in a Name?

When voters don’t know much about a candidate, name recognition plays a role in how they cast their ballots. Names that sound familiar, are easier to read or are “less strange” often get voter preference.

For example, Gene Kelly—no, not the actor, but a little-known lawyer—repeatedly sought the Democratic Party nomination for statewide offices in the

1990s and 2000s. At various times, he was nominated for positions on both of Texas’ two high courts.

Xavier Rodriguez had been appointed to the Texas Supreme Court by then-Gov. George W. Bush. He was up for reelection in 2002, but was defeated in the Republican primary by Steven Wayne Smith. Virtually all political commentators concluded at the time that “ballot names,” not qualifications, determined the outcome of that race. Rodriguez was later appointed as a U.S. district judge, where he still serves.

That same year, Ken Law defeated Lee Yeakel in the Republican primary for a seat on the Austin Court of Appeals. Yeakel had been on the court for about five years, was chief justice, and had broad support in the legal community. Law, on the other hand, filed for the seat at the last minute and raised virtually no money during the campaign. Law, it seems, is simply a better ballot name than Yeakel, especially in a judicial race. Yeakel was subsequently appointed to the federal bench, where he continues to serve.

Name recognition also undoubtedly played a role in the election of Scott Walker—not the well-known recent governor of Wisconsin—and Sam Houston Clinton to our state’s highest criminal appellate court. And a good, down-home sounding name probably accounts for Charlie Ben Howell’s electoral success, even though he was the subject of a contempt citation and a professional disciplinary lawsuit.

We do not wish to be understood as indicting the character or competence of judges who have prevailed in an election because of a good ballot name, but we do wish to be understood as indicting a system in which a person’s name—not their qualifications—determines who will decide whether a child is deprived of seeing a parent or an individual is sentenced to prison.

Texas’ Chief Justices Weigh In On Partisan Elections

During the 2019 legislative session, Rep. Brooks Landgraf (R-Odessa) filed House Joint Resolution 148 and House Bill 4504, establishing a new process to select judges to serve on the Texas Supreme Court, Court of Criminal Appeals, 14 intermediate courts of appeals, and state district courts in counties with a population exceeding a threshold to be set by the proposed statute.

Landgraf’s plan contained unique safeguards for the nonpartisan appointment of qualified men and women as judges, while preserving Texans’ right to vote to retain or remove judges based on their performance. The plan had four basic components: (1) the governor would nominate a person to a judicial vacancy, (2) a nonpartisan citizens board would rate that nominee as “unqualified,” “qualified” or “highly qualified,” (3) the Texas Senate would confirm the appointment with a two-thirds majority, and (4) the appointment would be for a 12-year term, with a nonpartisan, up-or-down “retention” election in the fourth and eighth years of each judge’s term.

In the House Judiciary & Civil Jurisprudence Committee hearing on this legislation, the current chief justice of the Texas Supreme Court and his two living predecessors testified in favor of changing the method Texas uses to select its judges. Their opening remarks to the committee are provided below (edited for length and clarity):

Nathan L. Hecht

(Chief Justice 2013-present; Justice 1989-2013)

I am Nathan Hecht, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Texas, speaking for myself on House Bill 4504 and House Joint Resolution 148.

Judicial selection has vexed the states since the days of the federal republic because it must balance judicial independence necessary for the integrity of the rule of law and judicial accountability owed the people for the stewardship of public office. If judges are to be completely true to the rule of law, applying it impartially without fear or favor, then they must be independent of the Legislature and executive, of politics and policy, of money and power, of friends and foes, of swings and the popular will. Divorce cases are not Republican or Democrat. Oil and gas cases are not left or right. Justice cannot be one thing for the wealthy and powerful, and another for the poor and marginalized. Judges must do equal right to all.

At the same time, judges—just like all public officials—must account to the people for their stewardship of power. You account to your constituents for advancing their interests. Judges have no constituencies. They account to the people for their adherence to the rule of law. When judges follow the law, even against the popular will of the time—especially against the popular will of the time—they have done their job. But when accountability is measured by whether a judge decides cases the way people like, or by what parties, contributors or friends like, and what they like is different from what the law is, the pressure is on the judge to surrender independence and the law to popular will and to take sides. Nothing can be further from justice.

The accountability component of the Texas system has utterly failed in urban areas. Judges are not elected or rejected on their merits but on whether they run in the same party as the governor, the U.S. Senator or the president. No one—literally no one— knows the dozens of judges on the ballot in urban areas. Not lawyers; certainly not voters. Voters do not know whether a judge has done a good job or a bad job, or whether a challenger will do better or worse. They vote for the party, or a catchy name, or they don’t vote.

The lack of judicial accountability in urban areas is bad because the basic rationale for the Texas partisan judicial elections has failed a large part of the state. That’s not the end of the justice system. If people don’t want effective accountability, it’s their choice. But the threat to judicial independence, that is the end of the justice system. If you want judges that rule in favor of the Republicans or the Democrats, in favor of the left or the right, in favor of the establishment or the outsiders, in favor of the rich or the poor, then we should keep partisan judicial elections. But be clear, today, tomorrow, or the day after, the powerful will win that struggle.

Polls show that everyone thinks—people, lawyers and even judges themselves—everyone thinks by overwhelming margins that political partisanship and campaign contributions affect judges’ decisions. Mostly they are wrong. In almost all of the eight million cases our 3,200 judges decide each year, Texas judges honor their oath and do the right thing. But a few times—and even a few are too many—people’s suspicions are right. Regardless of the facts, that perception mars the sacred face of justice.

I said that in this year’s State of the Judiciary Address. I won’t read it all back to you. I said the same thing in my 2017 address. I won’t read that either. I said exactly the same thing in my 2015 address, and I won’t read that. I’ve been a judge for almost 38 years, and I’ve been on ballots some 20 times. Partisan election of judges has been good for me, yet I’ve spoken against it since I was licensed to practice law 45 years ago. In the ‘90s when Texas was turning red, I supported repeated bipartisan efforts of Sen. Robert Duncan, who is here today, Sen. Rodney Ellis and my great friend Lt. Gov. Bob Bullock to change judicial selection. [Editor’s Note: Robert Duncan served as a Republican and Rodney Ellis and Bob Bullock served as Democrats.]

At some point, people who love the state and the rule of law—which I’ve championed for the poor all over the country—must say enough is enough. No state in history has found a perfect judicial selection system. The details will always be debated. House Bill 4504 gives the political system a role in gubernatorial appointments and Senate confirmation, looks to merits in the advisory board’s assessments, and provides accountability to the people in retention elections every four years. It is a responsible proposal.

I come before you, the national advocate for justice for the poor, justice for all. Last Tuesday, I was in Washington at the Supreme Court of the United States advocating with Justice Elena Kagan and lawmakers of all stripes for justice for all, just as I did with Justice Scalia when he was alive. This issue before you is whether to reform the Texas judicial selection system for the good of all of the causes.

Wallace B. Jefferson

(Chief Justice 2004-2013; Justice 2001-2004)

Good morning Chairman Leach, Vice Chair Farrar, and members. I’m Wallace B. Jefferson, I served on the Supreme Court of Texas from 2001 to 2013 and for almost 10 years as chief justice. I am currently a lawyer with Alexander Dubose and Jefferson here in Austin. I’m here to testify for the bill both personally and on behalf of the group Citizens for Judicial Excellence in Texas. I want to spend my time answering your questions, so I just have a very brief background.

When I first came to the court I came from private practice. I was a private citizen. I didn’t know anything about elections. I had never been in public office before. I had not been involved in partisan politics. I was an appellate advocate arguing before the U.S. Supreme Court, the Texas Supreme Court … and in the various courts of appeals around this state and this circuit.

When I began my campaign, I started going around the state, and the very first surprise to me was that people didn’t know that they elect judges. I would say, “I am running to retain my seat as a justice on the Supreme Court,” and they would say,“We elect judges?” They didn’t know. Common citizens didn’t know, and I think the reason was that they were voting straight partisan ticket, either for Republicans or for Democrats, without regard to the qualifications of the candidate. A straight ticket would get judges on the bench, and I found that to be surprising.

The other big surprise to me was the amount of money that was involved in these judicial races and how the citizens that I talked to were offended by the notion that I would be asking lawyers and companies that appear before my court to give me money to stay on the court. They thought that was unfair and unjust. Many of them didn’t have the resources to contribute to judicial campaigns, so I was thinking that this was a very bizarre system.

I understand the idea behind it. The idea behind it is that I’m no better than anyone else on the court, and I have to come to the voters and be accountable to the voters. I understood that. But the accountability factor broke down because people didn’t know who I was, and even that they were voting for me. This played out in every election that I had on the bench. In 2002, in 2006 and in 2008.

When I campaigned in 2008, it was when President Obama—then, candidate Obama—was on the ticket. I was very concerned at that point because I was running as a Republican for chief justice and the then-candidate Obama was bringing huge crowds. There was a Democrat insurgence, and it was exciting in many ways for me, the first African American to be on the Texas Supreme Court, to see this happening on the top of the ticket. But how was I going to win my election? It wasn’t because people knew who I was.

So I put together campaign TV ads, and the opening of the advertisement on TV was “Wallace Jefferson, chief justice of Texas. His ancestor was a slave owned by a state court judge, and today he is Supreme Court chief justice. Only in America.” It was a marketing plan to try to draw Democrats over to my race. It wasn’t based really on merit. It was based on passion. You are trying to get people emotionally involved behind the campaign.

And that has brought me to the conclusion that we need to find a system in which people who first come to the bench come because of their talents, not because of their politics. Because of their work ethic, not because of the money they raised. Because they are fair, not because they have the right name in a particular election. That is my concern. It has not been just my concern; it was Chief Justice Calvert’s, it was Chief Justice Hill’s, it was Tom Phillips’ and Nathan Hecht’s. It was Democrats and Republicans who said we can do a better job of finding talented men and women to serve on the judiciary.

I believe that the new judges—this is exciting to me—we are bringing in, through the electoral process—African Americans, in my home town in Bexar County we are bringing in Hispanic women—this is a good thing, not a bad thing. The question is, when the next election comes around, Trump will be on the ballot in 2020: will Texans vote for Trump and then vote for every Republican down the ballot and replace these new and talented judges, not based on how they have performed but based on party affiliation? That is why I am for a revolution in the way that judges come to the bench.

Thomas R. Phillips

(Chief Justice 1988-2004)

I was a district judge from 1981 to 1988 and chief justice [of the Supreme Court of Texas] from 1988 to 2004. I currently practice law here in Austin at the law firm Baker Botts. I am for the bill, and I am testifying both on my own behalf and Citizens for Judicial Excellence in Texas.

The system we have now is hurting the state of Texas, in my opinion. Form needs to follow function, and the judiciary is inherently and fundamentally different from the political branches in terms of what you are supposed to do and what the qualifications are. I agree that a lot of people don’t know their legislators, but when you have that party label, there is some expectation that you’re going to vote for a person who is going to behave in a certain way, broadly speaking, over a broad range of issues. There is no such expectation with the judiciary, particularly at the trial levels and the intermediate appellate level. You could make an argument on the Supreme Court—because of all the rules they write and the committees they appoint—that maybe there is some philosophical leanings there, but for the vast majority of our judges this party label is misleading.

You can see it with the number of people, both urban and rural, who have run on both parties at different elections. One poor guy in Houston ran as a Democrat, then as a Republican, then a Democrat, then a Republican, and he was trying in the 70s to get elected, and he picked the wrong one every time. No legislative candidate would switch three times. You’d be laughed off the stage. For a judge, he just wanted to serve. I think we start out fundamentally misleading people. When you add to that the high cost of these elections and the constant politicking, we are really hurting public confidence in the judiciary.

Texas is simply too important to settle for a judiciary that worked fine in 1849 when the voters voted to have the partisan selection system. We were a part of a big trend nationwide. By the end of the 19th century, three quarters of the states elected their judges. They weren’t even thinking partisan or nonpartisan, but the ballots were starting to be printed by the state, so they became partisan. Now, there are only six states that elect their Supreme Court on a party ballot and very few other than that elect lower [court judges]. And only Louisiana, Alabama and North Carolina join Texas in electing and reelecting trial and appellate judges on a party ballot. It is simply an idea whose time has passed.

My colleagues can tell you what I’ve experienced when I went to international conferences or even national conferences, and that there is a presumption against a Texas judge. When a Texas judge leaves the bench and talks about being an arbitrator, not just in Texas but nationally or internationally, there is a presumption that you aren’t fair because you’ve come out of this system… that was the subject of two 60 Minutes programs called “Justice For Sale” and what has been critiqued in the New York Times as “what passes for justice in small Latin American countries run by colonels in mirrored sunglasses.”

Out-of-state and out-of-nation litigants try to apply some other law, or try to get in some other forum far too frequently. This is bad for our state. This is very bad for the 10th largest economy in the world… For the good of the state… It is your place at this time to give as much attention as time will allow you to do and to think of a way we can help all of the people of the state by improving the judiciary in actuality and in perceptions. When litigants come before the court they cannot say, “I lost because of politics,” or, “I lost because the judge had never tried a case before.” They’ll know we are giving them the best system that imperfect humans can devise.